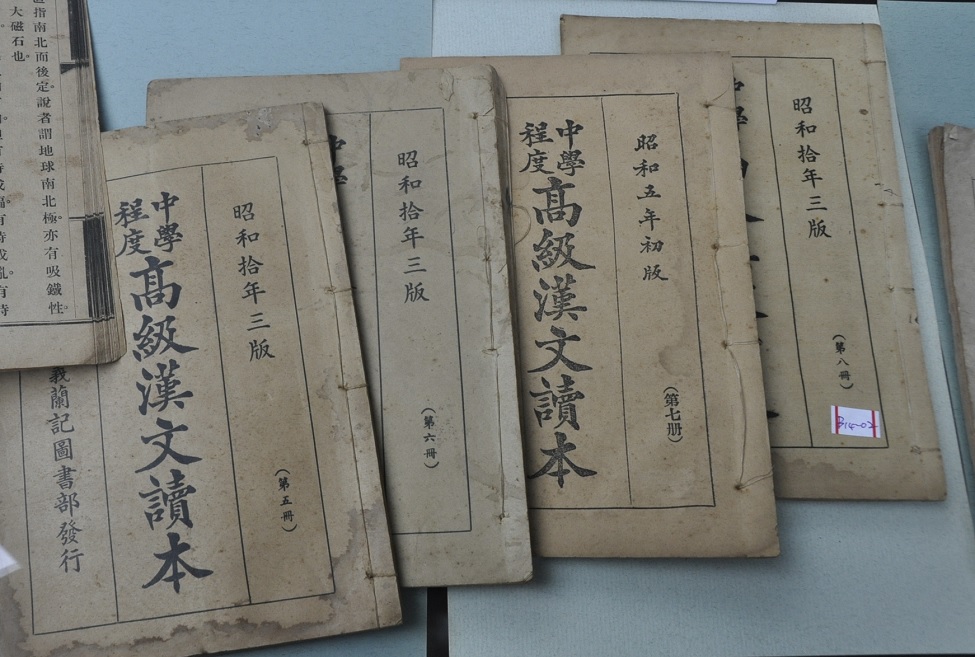

Niitakadō was also well known for issuing textbooks, reference tools, photograph collections, postcards, maps, and many other items. His [Utsumi's] taste for books also reflected an aspect of the marketing strategy of books, which was developed to cater to the growing needs of Japanese communities in Taiwan. An expanding readership on the island - across race and generation - was constructing "Taiwan" as a subject of Japan's empire. (p. 152)

Tuesday, August 30, 2022

Some notes on bookstores in Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period

Monday, August 29, 2022

Links to sources on the history vs. social science debate of August 2022

I'm not going to comment on any of this because I'm not following it closely enough, but I wanted to list out some links to various texts in the debate about history and empiricism and social sciences (particularly economics) that have been going on. I'm not going to link to all the Twitter threads right now (this one was funny), though I'm trying to bookmark some of them, but I'll just list out some of the blog posts I've read or skimmed.

The reason I'm doing this is mainly for ENGW 3315, the interdisciplinary writing course I teach fairly regularly. One of the things we get into is how different disciplines have different epistemological stances and "visions of reality," and some of what is going on in this discussion is about that.

Here are some of the articles:

- "On the Wisdom of Historians" by Noah Smith (8/26)

- "New Acquisitions: On the Wisdom of Noah Smith" by Bruce Devereaux (8/29)

- more to come...

Sunday, August 28, 2022

Notes on Lien Heng (1878-1936): Taiwan's Search for Identity and Tradition

Wu, Shu-hui. Lien Heng (1878-1936): Taiwan's Search for Identity and Tradition. Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, Indiana University, 2005.

This isn't going to be a formal review of Wu's biography of Lien Heng. There are two published reviews that I have found:

- Harrison, Mark. Review of Lien Heng (1878-1836): Taiwan's Search for Identity and Tradition, by Shu-hui Wu. The China Quarterly, vol. 187, 2006, pp. 800-802. https://doi.org/10.1017/S030574100639042X

- Salát, Gergely. Review of Lien Heng (1878-1836): Taiwan's Search for Identity and Tradition, by Shu-hui Wu. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, vol. 66, no. 3, 2013, pp. 488-489. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43282533

as in each case the functional placement of the text is as an officially placed critique of the policies of authorities in higher positions. Such a comparison would depend on first making a linguistic, cultural, epoch-internal contrast among information, critical, and expressive genres in government and official social contexts. (p. 354)

The colonial administrators had an extensive network designed to control Taiwanese thought and they exercised this without consulting the constitution of their home government. Especially onerous was the rigid control of the sale of books. When books arrived from China, they were subjected to censorship at the customs house. Those books belonging to restricted categories (chin-shu) were removed from their packages and confiscated. Usually, the loss from each order was around thirty to sixty percent. Worse was that the restriction standards changed constantly. Very often books became illegal after the bookstores had sent in their orders and it was too late to inform the publishers in China because the goods had already been shipped. It took months for the books to travel to Taiwan. Sometimes customs would pull only one or two volumes from a multi-volume set and make the entire collection impossible to sell. The biggest threat to a bookstore owner was the unexpected inspections conducted by the police. The owner would be fined and imprisoned for several days or weeks if he violated the law, even if his store just held books in storage that were on the new banned list. Chiang Wei-shui's store was often monitored by the secret police because of his political and social activities. (pp. 254-255)

A webpage about bookstores in Taiwan mentions that during the Japanese period, there were only about 30 bookstores in colonial Taiwan. Taichung's Central Bookstore (中央書局) was one of those; the Wikipedia article about the store, which opened up in 1927 (around the same time Lien's store opened), says that at that time, it was the first bookstore in Central Taiwan specializing in importing Chinese and Japanese books and magazines and was also the largest Chinese bookstore in Taiwan. It ran into trouble after the Mukden Incident of 1931.

For Liang, the Japanese language was little different from Cantonese. Both were rooted, he believed, in an ancient literary language, wenyan, which had served both countries (and Korea and Vietnam, it should be added) for many centuries. The Hewen Han dufa (Reading Japanese the Chinese way), a contemporary work offering easy access to Japanese for readers of Chinese, was an all-important text for Liang. It not only enabled him to gain quick entry into contemporary Japanese writings and translations; it also substantiated the notion that Japanese could be read as if it were a topolect of Chinese. (249-250)

From Joshua A. Fogel, "Introduction: Liang Qichao and Japan." Between China and Japan: The Writings of Joshua Fogel, Brill, 2015. 242-252. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004285309_017

Thursday, August 18, 2022

Casting about for my next reading project

The fall semester is going to start soon, so I'm busy preparing my three classes (two sections of first-year writing for multilingual students and one section of business writing for multilingual students), but I'm also interested in getting into another book. I finally (FINALLY!) finished John Robert Shepherd's Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600-1800, which I see I mentioned starting in June of 2021(!).

As you can imagine, I've forgotten a lot of the details in the book (of which there are many). As I wrote in a text back in May to someone more well-read in Taiwan history than I am, "My main takeaway so far is that it doesn't seem at all that the Qing were ignoring Taiwan the way the popular imagination seems to have it. (Not to say that their governing was super effective.)" That's still my main conclusion--obviously the Qing didn't control most of Taiwan; Paul Barclay's book Outcasts of Empire: Japan’s Rule on Taiwan’s “Savage Border,” 1874–1945 explains Qing rule in terms of "multicentric legal pluralism" (p. 17), where "heterogeneous communities and ranked status groups stood in differentiated legal relationships to the apical center of authority in Beijing. Implicit in the notion of multicentric legal pluralism is the possibility that sovereignty can be graded, and even diminished, at the margins of a polity" (p. 17). This accounts for the Qing's initial response to, for instance, Japanese protests in the aftermath of the Mudan village incident of 1871 in which Paiwanese villagers killed 54 Okinawan survivors of a shipwreck in southern Taiwan. But, getting back to Shepherd, I think his book shows that the Qing did not "neglect" the parts of Taiwan over which they ruled.

Shepherd's book is almost 30 years old, though, so I would like to read something more recent that might supplement my knowledge. I started to read Barclay's book a while back, so that's one possibility, though its focus is mostly on the Japanese period. University of Washington professor James Lin also asks students in his graduate survey of Taiwan studies to read Tonio Andrade's How Taiwan Became Chinese, though that seems to end with the fall of the Dutch colony. I could reread Emma Teng's Taiwan's Imagined Geography, though I think I'd rather spend my time reading something new. Any recommendations?

[Update, Aug. 19: I ended up choosing Lien Heng (1978-1936): Taiwan's Search for Identity and Tradition, by Shu-hui Wu (mainly because it was within reach...). So far it's interesting reading, though there are a couple of details that have puzzled me. Maybe I'll write more about that when I finish the book.]

Monday, August 15, 2022

Ti Wei & Fran Martin, "Pedagogies of food and ethical personhood: TV cooking shows in postwar Taiwan"

Number nine in an occasional series of summaries of articles related to communication practices in Taiwan.

Wei, T., & Martin, F. (2015). Pedagogies of food and ethical personhood: TV cooking shows in postwar Taiwan. Asian Journal of Communication, 25(6), 636-651, DOI: 10.1080/01292986.2015.1007333

This article uses representative cooking personalities on Taiwanese TV--Fu Pei Mei (傅培梅), Chen Hong (陳鴻), and Master Ah-Ji (阿基師), together with Chef James (詹姆士)--to analyze "the history and changing cultural meanings of the cooking show in the context of Taiwan’s postwar social history and TV industry" (p. 637). The authors trace the transformation of television programming in Taiwan from its start in the martial law period to the commercialization of the industry in the post-martial law years, including the rise of cable TV. They show how the representative cooking shows reflected both changing industry priorities and some consistency in cultural values. They also contrast the more paternalistic authoritative approach to imparting lessons in cooking and "life ethics" in Taiwan with an ethics based on more "plural, practice-based everyday knowledges" that researchers have found in Western cooking shows (p. 637).

In the case of Fu Pei Mei, the authors observe that her shows, which started in the early 1960s, reflected the KMT's goals of teaching the audience to see themselves as part of the Chinese nation. Fu's emphasis on mainland Chinese cultural traditions in her shows and in interviews with domestic and international audiences made her a representative of the KMT government's "soft power" in the ideological battle with the CCP (p. 641). At the same time, the authors argue that she represented a kind of modernity through her own image as an "autonomous, modern woman," as well as through her introduction of "modern" (Western cooking). As they conclude, Fu's image "can be seen as a fusion of traditional and modern elements of femininity" (p. 641).

In comparison to Fu Pei Mei, Chen Hong's image, according to Wei and Martin, models "cosmopolitan taste, high cultural capital, and refined masculinity[, which] bespeaks an implicit pedagogical project centered on the production of a clearly (middle-)class-inflected aspirational ideal of young, urban, educated personhood" (p. 642). In addition, Chen also "reinforces his own authority" through his lessons in cooking and references to classical Chinese works (p. 644). Chen's image as a 型男 (which the authors translate as metrosexual) coincided with a rise in consumerism in post-martial law Taiwan that commodified cultural knowledge as cultural capital; it also fit in with the rising competitive cable media landscape.

The last cooking program that Wei and Martin examine reflects the consolidation of the cable industry in Taiwan and the increasing competition for viewers that resulted in an emphasis in lifestyle programming on entertainment over information. In this media landscape, cooking shows like Metrosexual Uber-Chef (型男大主廚) tended to stress entertaining audiences over teaching them about cooking or inculcating ethical values. While Master Ah-Ji, the older chef paired with the younger "metrosexual" James in the program, represents traditional values such as "frugality, endurance, obedience, and so on" (p. 647), in the context of a more postmodern and entertainment-oriented show, "[t]his older discourse of the ‘self-made man’ was thus unexpectedly effectively – or perhaps, absurdly – fused into a postmodern form of entertainment TV" (p. 647). Master Ah-Ji maintains, argue the authors, a different kind of cultural capital than the two previous chefs--one that reflects the values of an industrializing Taiwan of the 1970s.

One thing that the article made me think about was the evolution of the pedagogical project of Chineseness that they suggest characterized Fu Pei Mei's shows. It's interesting that, according to the authors, an important part of Fu's cultural pedagogy connected her audience to the Chinese mainland (they quote her as frequently saying, "we northerners" when referring to her own background); being Chinese, in this sense, was concretely tied to the KMT project of "mainland-izing" Taiwan by emphasizing geographic relations as well as culinary connections. I'm reminded, in fact, of PRC foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying's widely mocked tweet arguing for the PRC's sovereignty over Taiwan based on the large number of Shandong dumpling places and Shanxi noodle restaurants in Taipei.

As Rachel Cheung observes, the tweet found a receptive domestic audience. Cheung quotes scholar Gina Anne Tam, who argues that domestic Twitter users were Hua's primary audience, and the tweet was calculated "to muddy a logically indefensible case with appeals to vague feelings." And, as Cheung notes, these emotional/culinary appeals were further supported by observations that many of Taipei's own streets have been named after Chinese locations (a project that was also part of the KMT's "mainland-ization" of Taiwan during the martial law period). It appears, then, that the culinary/geographic connections exemplified by Fu Pei Mei's cooking programs have come full circle.In contrast to Fu's appeals to geography, in Chen Hong's work, Chineseness is represented by references to classical texts and sayings. As the Wei and Martin suggest, "the ethical dimension connects with the value of literary education" (p. 644). In a sense, then, Chinese identity as represented by Chen Hong is based on shared texts. Arguably--at least based on Wei and Martin's descriptions of the programs--Ah Ji's authority is the most rooted in the particularities of Taiwan's late martial law historical context, since it appears that he reflects the values that purportedly built Taiwan's "economic miracle." This appears to be less based on an appeal to a common Chinese (in terms of mainland-based) identity and more on an appeal to the common experiences of the people of Taiwan.

Another point to raise regarding Ah-Ji is his "fall from grace" subsequent to a 2014 scandal reported in Next Magazine. According to Wikipedia, there is some controversy over whether he intentionally stepped away from the media, but it appears he is no longer a television personality. He appears, however, to have a following on Facebook, which suggests how Wei and Martin's article might be followed up in the future, in regards to how social media might contribute to the further evolution of cooking shows in Taiwan. (In the TTV program linked to below, Chen Hong touches on social media and "self-media" [自媒體] and how it has changed the media landscape and how it affects self-promotion and interaction.)

One final point: the authors describe Chen Hong as losing popularity in Taiwan after 2005. That might be the case, but more interesting are the recent developments in his professional life. Ah-Hong (陳鴻) has evidently expanded his audiences to Southeast Asia in addition to Taiwan, suggesting an appeal to "Greater China" and "Overseas Chinese." In this program about him from TTV, he talks about the challenges of life, arguing that they have taught him important life lessons that he is grateful for (and indirectly teaching viewers to consider the lessons he has learned).

In addition, the reception in Taiwan of Ah-Hong's openness about his sexuality suggests a further development in the relationship of celebrity and "ethical personhood" in Taiwan. There are probably articles about this (guess I should look for them), but the general acceptance (with some vocal exceptions) of LGBTQ people in Taiwan is reflected in, and perhaps encouraged by, the visibility of public figures such as Ah-Hong and others who have been public about their sexuality. In addition to Ah-Hong, I think of Li Jing 利菁, for instance--"Taiwan's first mainstream transgender entertainer," and Audrey Tang 唐鳳, Taiwan's first transgender cabinet official. Their openness could be described as a kind of pedagogy of ethical personhood that has contributed to Taiwan's status as the most LGBTQ-friendly country in Asia.