Sunday my wife and I went to a screening of Will Tiao's movie, Formosa Betrayed. Based on historical events, it tells the story of an American FBI agent sent to Taiwan in 1983 after a Taiwanese-American professor is murdered in the US. The agent quickly finds himself in over his head as he balances his desire to get to the bottom of the murder with the pressures on him coming from the US and from the martial law government in Taiwan. After witnessing (and experiencing) the brutality that the US-supported government visits upon the pro-democracy Taiwanese citizens, and after getting no help from the American liaison in Taiwan, Agent Jake Kelly returns to the US and, disillusioned, quits the FBI.

We'd seen the film before (in fact, we have a DVD of it), but what drew us into Cambridge was the chance to see Tiao (writer, producer, and actor in the movie) and ask him some questions during an after-screening Q&A session.

There was a good crowd in the church. The people who were there--at least the ones who asked questions--didn't seem to know very much about Taiwan's history, so I was hesitant to ask the questions I came to ask, preferring to hear the rest of the audience ask their questions about Taiwan's history. It was gratifying to see how interested they were after watching the movie. I think that's Tiao's point. As he said, Taiwan is basically the only reason that might lead the US and China into an armed conflict (though I think I'd phrase that differently, as China's attitude or actions regarding Taiwan are the only reasons), so it's important that Americans have some understanding about the status and history of the island. While this movie is a fictionalized representation of the kinds of events that actually took place during the martial law period in Taiwan (which only ended in 1987), it does a service to the cause of helping Americans understand some of the recent history of Taiwan.

I asked Tiao about what the main character Jake Kelly would do next, and he kind of laughed and said, maybe join an NGO? He talked about how Jake represented friends of his growing up who had an idealistic notion of how democracy was supposed to work and then found out that it's not working the way that you'd hope that it would. I think Jake is in some ways a George Kerr-type figure, though Kerr knew more about what was going on in Taiwan than Jake does at the beginning of the movie. Jake's also sort of a Ralph Barton figure (though Tiao told me he never read Vern Sneider's novel, A Pail of Oysters). They all (including Kerr, actually) come to know Taiwan and the Taiwanese through personal relationships, and it's through the suffering of those people they've come to love that they are given a different perspective on how things are actually operating there. Their later commitment to Taiwan also grows out of the suffering of their loved ones. My guess is that Jake Kelly is going to write articles or a book about what happened, or start to make public speeches about what he saw and experienced, much as Barton commits to doing at the end of Vern Sneider's novel. (Some people might find it amusing that I'm speculating about the future of a fictional character, but I think it's worthwhile to think about the trajectory the plot would take if the story continued, particularly when the story is based on real and contemporary events.)

Interestingly, an earlier treatment that I quoted years ago from the movie's website concludes with Kelly "return[ing] to the States, frustrated with his knowledge and lack of

power to do anything about it—when he is invited to testify before the

U.S. Congress in Washington D.C. and finally given the chance to declare

the truth." This last part didn't actually happen in the final version. I wish I had had the chance to ask Tiao about the change to the ending. Maybe he'll comment on this post and let me know what led to the decision to change the ending. Thanks in advance, Will!

It was also fascinating to find out that Tiao grew up in Manhattan, Kansas, where his parents were graduate students. I had read several years ago that there was a lot of Taiwan Independence activity at KSU in the mid 1960s (see the oral history, 一門留美學生的建國故事, for details), but I hadn't yet met anyone who was that close to such activity. He mentioned that KSU was often referred to as the 'military school for Taiwan independence' (台獨軍校).

Anyway, it was good to see the movie as a member of an audience larger than two people, and the opportunity to talk to the man responsible for putting it together was great. Thanks to Karin Lin for organizing this event!

Monday, October 07, 2013

Sunday, May 05, 2013

Starting summer courses tomorrow

The spring semester here ends in mid-April, which means that a lecturer like me typically wouldn't see a paycheck between the end of April and the middle of September. This summer, though, I've picked up two courses in the first summer session. This will supplement our income nicely.

I've taught summer courses before, but never two intensive writing courses at the same time. Fortunately, I've taught both of these courses before (a first-year composition course for multilingual students and an advanced writing course, also for multilingual students). I'm using the "lighter"(?) summer load to do a little experimenting with how I'm running the course, in hopes that I'll figure out some better ways of evaluating and grading students' work, particularly in the murky areas of peer work and journal writing. We'll see how this works out.

I've been fortunate to land a job here at a school where I can work a lot with international students. I've also had some good classes with USAmerican students, but I feel my strengths are really in working with students from other countries. Like some of them, I sometimes feel like a bit of an outsider in the US and find that "alternative" ways of doing things or thinking about things are not always accepted, tolerated, or even understood.

Well, I've meandered pretty far from the topic of summer school starting tomorrow.

Update, 5/6/13, 6:18 p.m.: Speaking of meandering, this afternoon I fell asleep on the commuter rail and missed my stop. Ended up having to walk 2 miles to get home. (Good exercise!)

I've taught summer courses before, but never two intensive writing courses at the same time. Fortunately, I've taught both of these courses before (a first-year composition course for multilingual students and an advanced writing course, also for multilingual students). I'm using the "lighter"(?) summer load to do a little experimenting with how I'm running the course, in hopes that I'll figure out some better ways of evaluating and grading students' work, particularly in the murky areas of peer work and journal writing. We'll see how this works out.

I've been fortunate to land a job here at a school where I can work a lot with international students. I've also had some good classes with USAmerican students, but I feel my strengths are really in working with students from other countries. Like some of them, I sometimes feel like a bit of an outsider in the US and find that "alternative" ways of doing things or thinking about things are not always accepted, tolerated, or even understood.

Well, I've meandered pretty far from the topic of summer school starting tomorrow.

Update, 5/6/13, 6:18 p.m.: Speaking of meandering, this afternoon I fell asleep on the commuter rail and missed my stop. Ended up having to walk 2 miles to get home. (Good exercise!)

Monday, April 08, 2013

Notes about chapter two of Asia as Method (part two)

Chen, Kuan-Hsing. "Decolonization: A Geocolonial Historical Materialism." Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2010. 65-113.

More quotables from this chapter:

Chen notes that in a later book entitled The Illegitimacy of Nationalism: Rabindranath Tagore and the Politics of Self (1994), Nandy "argues that nationalism is a by-product of colonialism, and that third-world nationalism buys into the belief that it is backward without the nation-state and nationalist sentiment. Nationalist independence movements are reactions against colonialism and are thus caught in a colonialist frame of mind, accepting that the formation of the nation-state is an inevitable stage in the evolutionary progress of mankind" (91).

After all of this (and some other things), Chen moves toward a conceptualization of what he calls "critical syncretism"--he introduces Edward T. Ch'ien's discussion of the syncretism of Ming Dynasty scholar Chiao Hung (Jiao Hong), which instead of treating Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism separately, mixes them and sees them as "'mutually explanatory and illuminating'" (Ch'ien 14, qtd in Chen 98). Chen goes on to suggest that this syncretism involves active agents who are "highly self-conscious when translating the limits of the self" (unlike with hybridity, which he calls "a product of the colonial machine's efforts toward assimilation") (98).

Calling critical syncretism "a cultural strategy of identification for subaltern subject groups" (99), Chen describes the goal of such a strategy as

More quotables from this chapter:

"Third-world nationalism, as a response and reaction to colonialism, was ... seen as an imposed but necessary historical choice, a choice made in order to affirm the new nation-states' autonomy from the colonizing forces" (82).Chen discusses Ashis Nandy's idea of "'the second form of colonization'" (Nandy 1983, xi):

"'Self-determination,' a slogan heralded by the younger generation of imperialist powers such as the United States, proved to be not so much a humanist concern, but a political strategy on the part of the imperialists to scramble the already occupied territories in order to secure for themselves a larger piece of the cake in the name of 'national interests.' J. A. Hobson, as early as 1902, had remarked on the close ties between nationalism and imperialism: the latter, he argued, cannot function without the former (Hobson 1965 [1902]). By the 1940s, it had become clear that neoimperialist nationalism was in good shape. Cesaire's Discourse on Colonialism warned third-world intellectuals not to be deceived by this rising new power. He argues that the rise of the United States signals a transition from colonialism to neo-imperialism, from territorial acquisition to 'remote control.' Occupied by their struggle to grasp state power, third-world nationalists did not seem bothered by the formation of U.S. hegemony; in fact, they prosecuted their struggle for independence with financial and military 'help' from the United States." (82)

"No longer presenting itself as the face of the colonizer, but instead relying on the superior imaginary of the West, the second wave of colonialism was able to exercise its power to change the cultural priorities in the formerly colonized society. The West was no longer a geographical and temporal entity, but a universal psychological category: 'the West is now everywhere, within the West and outside; in structures and in minds' (ibid.) Nandy's main agenda is to combat the hegemonic West by rediscovering cultural practices and traditions uncontaminated by colonialism." (Chen 89)

Chen notes that in a later book entitled The Illegitimacy of Nationalism: Rabindranath Tagore and the Politics of Self (1994), Nandy "argues that nationalism is a by-product of colonialism, and that third-world nationalism buys into the belief that it is backward without the nation-state and nationalist sentiment. Nationalist independence movements are reactions against colonialism and are thus caught in a colonialist frame of mind, accepting that the formation of the nation-state is an inevitable stage in the evolutionary progress of mankind" (91).

After all of this (and some other things), Chen moves toward a conceptualization of what he calls "critical syncretism"--he introduces Edward T. Ch'ien's discussion of the syncretism of Ming Dynasty scholar Chiao Hung (Jiao Hong), which instead of treating Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism separately, mixes them and sees them as "'mutually explanatory and illuminating'" (Ch'ien 14, qtd in Chen 98). Chen goes on to suggest that this syncretism involves active agents who are "highly self-conscious when translating the limits of the self" (unlike with hybridity, which he calls "a product of the colonial machine's efforts toward assimilation") (98).

Calling critical syncretism "a cultural strategy of identification for subaltern subject groups" (99), Chen describes the goal of such a strategy as

"to actively interiorize elements of others into the subjectivity of the self as as to move beyond the boundaries and divisive positions historically constructed by colonial power relations in the form of patriarchy, capitalism, racism, chauvinism, heterosexism, or nationalistic xenophobia" (99)."Becoming others," he writes, "is to become female, aboriginal, homosexual, transsexual, working class, and poor; it is to become animal, third world, and African" (99). I have to admit that when I read this I think of a speech by Richard Rodriguez from 1999, in which Rodriguez argues that he is more Irish than Mexican (due to the education he received from Irish nuns) and is Chinese by virtue of living among Chinese. Rodriguez asks his audience, "What if I find myself becoming you?" I wonder how Chen would respond to Rodriguez's take on identity...

Saturday, March 30, 2013

Notes about chapter two of Asia as Method (part one)

Chen, Kuan-Hsing. "Decolonization: A Geocolonial Historical Materialism." Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2010. 65-113.

A few quotes about what he's up to in this long chapter:

Part of this chapter makes use of three sources that represent three forms of decolonization, according to Chen: Frantz Fanon, who critiques nationalism "at the peak of the third-world independence movement in the 1950s and 1960s" (67); Albert Memmi, who critiques nativism; and Ashis Nandy, who proposes what Chen calls a "civilizationalism" that "is nonstatist and counterhegemonic" (94).

Chen brings in arguments about the psychic dimensions of colonialism, "colonial identification," and the struggle for decolonization:

Arguing that Fanon was aware of "multiple structures of domination," Chen argues that "[M]any postcolonial theorists focus on a singular structure of domination--along the continuum of race, ethnicity, nation, and civilization--and are unwilling to bring other structures into the picture. But if structures of domination have historically always been interlinked and mutually referencing, then colonial structures are necessarily entangled with other structures of power" (80, my emphasis).

More later...

A few quotes about what he's up to in this long chapter:

In this chapter, I propose geocolonial historical materialism as a framework for analyzing the problematic of decolonization in relation to cultural formation in formerly colonized spaces. (65)

The first task of the geocolonial historical materialist framework proposed in this chapter will be to work through the third-world discourse on colonial identification in order to first situate geocolonial historical materialism within cultural studies, and then to make the theoretical move to connect it with the spatial turn, a move inspired by radical geography. This chapter is a theoretical exercise that aims to connect and reconnect with these discursive traditions by tracing selected responses to colonialism after the Second World War; it is concerned essentially with the problems within former colonies. (66)

Part of this chapter makes use of three sources that represent three forms of decolonization, according to Chen: Frantz Fanon, who critiques nationalism "at the peak of the third-world independence movement in the 1950s and 1960s" (67); Albert Memmi, who critiques nativism; and Ashis Nandy, who proposes what Chen calls a "civilizationalism" that "is nonstatist and counterhegemonic" (94).

Chen brings in arguments about the psychic dimensions of colonialism, "colonial identification," and the struggle for decolonization:

The well-documented experiences of contemporary social movements suggest that the pain of struggle is always inscribed on the psychic body. Regarded as a personal and sometimes a shameful matter, the issue of recurring psychic suffering is rarely openly discussed, but if lessons about this psychic realm are not learned and shared, the problems will continue to return. Similarly, to fully understand the violence of the colonial condition, we need to enter this same psychic space. Hence, the psychoanalysis of colonization and decolonizing psychoanalysis are one and the same process. (73)Continuing in this psychological vein, and citing Françoise Vergès,Chen argues that

the epistemological foundation of colonial psychology was the political unconscious of family romance: the relationship between parents and children. The colonized subjects were essentialized as being poor in linguistic expression and lacking the capacity for clear conceptualization: they believed in supernatural powers; they were fatalistic; all their knowledge came from blind faith in their ancestors' superstitions; and therefore, these natives could not mature unaided into adulthood. The colonizer's mission was to guide them. Of course, this entire formulation hid behind the name of science, and the validity of the psychologist's observation was backed by the guarantee of scientific neutrality. (74)Chen observes that in Black Skin, White Masks, "Fanon puts Lacan's 'mirror stage' theory in the colonial context. Although subjectivity is always mutually constituting, the colonial history of economic domination has put the entire symbolic order in the hands of the white colonials, making them the defining agents of the ideological structure. The position occupied by the whites reduces blacks to the level of biological color alone. For the white subject, this bodily difference marks the boundary of the white subject. It has nothing to do with history or economics but is a 'universal' difference" (78-9).

Arguing that Fanon was aware of "multiple structures of domination," Chen argues that "[M]any postcolonial theorists focus on a singular structure of domination--along the continuum of race, ethnicity, nation, and civilization--and are unwilling to bring other structures into the picture. But if structures of domination have historically always been interlinked and mutually referencing, then colonial structures are necessarily entangled with other structures of power" (80, my emphasis).

More later...

Monday, March 25, 2013

Why 外 not?

I haven't written much about my "return" to the US in 2011--I'm not even sure I

am comfortable calling it a "return" because that implies sort of a

sameness about me and about the US that isn't the case. I enjoyed

reading Mark Wilbur's post on "Returning to America," though, because I

had some of the same feelings as he did after he came back to the US

after years of living abroad (particularly the feeling of going back in

time whenever I'm at the commuter rail or subway stations!).

One difference between living in Taiwan and living here is that I no longer see this on my Starbucks cups:

So I guess I'm saying I'm not seen as a 老外 anymore--at least not here. (And of course I'm a fan of cheesy bilingual puns, too.)

One difference between living in Taiwan and living here is that I no longer see this on my Starbucks cups:

| |||

| It's not clear, but it says 老外. |

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

More on Freshman Chinese at Tunghai

About six and a half years ago, when this blog had another name, I posted a response to Kerim Friedman's comments about "Freshman Chinese"in which I described a project carried out by the Chinese Department at Tunghai designed to turn the first-year required Chinese course into more of a balanced reading and writing course. (Their official title is 中文, which simply translates to "Chinese.") Some of the goals of the course, as I noted then, were mentioned in the English abstract for the project proposal. They included the following:

There's a page linking to student writing, as well. I haven't gone through all of this writing (though it looks like it would be an interesting project), but I did glance at some of the essay titles from some of the colleges (the students are divided into courses by college, such as the College of Business, the College of Agriculture, etc.). In particular, I was trying to get a quick idea of the kinds of essays students were being asked to write. My interest came out of a recent article in College Composition and Communication in which the authors--Patrick Sullivan, Yufeng Zhang, and Fenglan Zheng--compare and contrast the teaching of college writing in the US and China. Zheng suggests that Chinese writing instruction stresses the aesthetic and stylistic qualities of writing--student writers should "observe and reflect consciously, describe scenes vividly, articulate thoughts and emotions accurately, and organize an essay strategically" (323--interesting parallel structure in that quote).

I was curious to see if the Chinese writing instruction at Tunghai had a similar focus, or if something else was going on. I was particularly curious to see if there was any kind of Writing in the Disciplines (WID) writing instruction in which students in, for instance, the College of Engineering might learn how to write like engineers. Judging from the quick look I took at the titles of some of the sample student writing, though, it appears that there isn't a lot of that going on, though there appears to be a variety of essay types being written. While there appears to be a lot of the more aesthetic sanwen (散文) being written, there are also some more persuasive texts, like some essays I found arguing about whether the death penalty should be abolished in Taiwan. (One that I looked at was written by a math major, another by a life sciences major, and the third by a chemical biology major.)

I also found the program-wide goals, or "Core Competencies," for these Freshman Chinese classes. They are the following:

This basically roughly translates as follows (corrections appreciated):

1) Analyze problems and appreciate literature, raise personal intellectual ability and sensitivity toward literary art

2) Master linguistic communicative abilities

3) Become equipped with critical thinking skills

4) Language proficiencies that correspond to the characteristics of each college

I was particularly curious about that last core competency, so I looked at the course descriptions for the 23 spring 2013 courses described as "加強寫作班" (courses focused on strengthening writing). Of the 23 course descriptions, 13 were described as helping students become linguistically proficient in ways that would correspond to their college's needs or characteristics. Of course, it's hard to tell what individual teachers mean by this--how they see their courses corresponding to those goals. Some courses seemed to be working with literary texts, even though the students were all from the College of Engineering. Not that engineers shouldn't read and write about literary texts--but I didn't see anything in that particular syllabus that seemed to correspond to the writing needs of engineers.

The course materials and sample student essays look interesting, though, and I'll have to take a closer look at them when I get a chance. It would also be interesting to see how this kind of writing instruction compares with Chinese writing instruction in other schools in Taiwan, and with writing instruction in Chinese universities.

Update, 4/5/13: I found a student essay entitled "巨大能量伴隨著巨大災害-核能運用的反思" ("Enormous Energy Accompanied by Enormous Disaster: A Reflection on the Use of Nuclear Energy") that cites a quote by Einstein. (This essay was written by a philosophy major.)

I also found an essay entitled "從<嘉平公子>看蒲松齡的社會背景與愛情觀" ("Seeing Pu Songling's Social Background and Views on Love from 'The Young Gentleman from Jiaping'") that has a 9 endnotes and an extensive bibliography of works cited and consulted. Another essay "探討<霍小玉>中所映照的唐代社會" (An Exploration of Tang Dynasty Society as Reflected in Huo Xiaoyu"), written for the same professor, also looks like a research paper. These are both analyzing literary works in relation to their social contexts (and they were both written by students in the Chinese Department).

So there are at least three essays that look like academic essays in which outside sources are footnoted and listed in bibliographies. There might be more, but I haven't had time to go through all of the essays. (Note that I'm not being critical of the other types of writings in this collection--the sanwen and poetry, for example--I'm just trying to get a sense of the range of genres in these "加強寫作班.")

The goal of Freshman Chinese is aimed at improving student’s language skills. However, the average size of 60 students per class makes it impossible for any teacher to help the students efficiently. Therefore, we decided to reduce the class size down to 30 students in the reading & writing class. For the first two years, we plan to offer 12 classes for the incoming students in the six different colleges, namely, the Colleges of Arts, Management, Social Science, Engineering, Science, and Agriculture. These classes focus on writing, but the theme and reading materials for each class is designed by individual instructor based on his or her specialty. We feel that this arrangement would allow individual instructor to demonstrate his or her teaching skills in a more effective way. Student writing could be creative or expository depending on the nature of the assigned topics. Each student is required to hand in at least 4 short papers and one research paper with substantial length each semester.Six years later, it looks like the program is still going, according to this webpage (Chinese). During the spring 2013 semester, there are 66 sections of first-year Chinese, of which 23 are classified as sections meant to reinforce or strengthen students' writing (加強寫作班). These sections are limited to 30 students (other sections can have up to 60 or more students).

There's a page linking to student writing, as well. I haven't gone through all of this writing (though it looks like it would be an interesting project), but I did glance at some of the essay titles from some of the colleges (the students are divided into courses by college, such as the College of Business, the College of Agriculture, etc.). In particular, I was trying to get a quick idea of the kinds of essays students were being asked to write. My interest came out of a recent article in College Composition and Communication in which the authors--Patrick Sullivan, Yufeng Zhang, and Fenglan Zheng--compare and contrast the teaching of college writing in the US and China. Zheng suggests that Chinese writing instruction stresses the aesthetic and stylistic qualities of writing--student writers should "observe and reflect consciously, describe scenes vividly, articulate thoughts and emotions accurately, and organize an essay strategically" (323--interesting parallel structure in that quote).

I was curious to see if the Chinese writing instruction at Tunghai had a similar focus, or if something else was going on. I was particularly curious to see if there was any kind of Writing in the Disciplines (WID) writing instruction in which students in, for instance, the College of Engineering might learn how to write like engineers. Judging from the quick look I took at the titles of some of the sample student writing, though, it appears that there isn't a lot of that going on, though there appears to be a variety of essay types being written. While there appears to be a lot of the more aesthetic sanwen (散文) being written, there are also some more persuasive texts, like some essays I found arguing about whether the death penalty should be abolished in Taiwan. (One that I looked at was written by a math major, another by a life sciences major, and the third by a chemical biology major.)

I also found the program-wide goals, or "Core Competencies," for these Freshman Chinese classes. They are the following:

| 1 | 分析問題與欣賞文藝,提升個人對文學藝術的知性和感性能力 | |

| 2 | 掌握語文表達能力 | |

| 3 | 具備思辨的內涵和能力 | |

| 4 | 對應各學院特色的語文應用能力 |

This basically roughly translates as follows (corrections appreciated):

1) Analyze problems and appreciate literature, raise personal intellectual ability and sensitivity toward literary art

2) Master linguistic communicative abilities

3) Become equipped with critical thinking skills

4) Language proficiencies that correspond to the characteristics of each college

I was particularly curious about that last core competency, so I looked at the course descriptions for the 23 spring 2013 courses described as "加強寫作班" (courses focused on strengthening writing). Of the 23 course descriptions, 13 were described as helping students become linguistically proficient in ways that would correspond to their college's needs or characteristics. Of course, it's hard to tell what individual teachers mean by this--how they see their courses corresponding to those goals. Some courses seemed to be working with literary texts, even though the students were all from the College of Engineering. Not that engineers shouldn't read and write about literary texts--but I didn't see anything in that particular syllabus that seemed to correspond to the writing needs of engineers.

The course materials and sample student essays look interesting, though, and I'll have to take a closer look at them when I get a chance. It would also be interesting to see how this kind of writing instruction compares with Chinese writing instruction in other schools in Taiwan, and with writing instruction in Chinese universities.

Update, 4/5/13: I found a student essay entitled "巨大能量伴隨著巨大災害-核能運用的反思" ("Enormous Energy Accompanied by Enormous Disaster: A Reflection on the Use of Nuclear Energy") that cites a quote by Einstein. (This essay was written by a philosophy major.)

I also found an essay entitled "從<嘉平公子>看蒲松齡的社會背景與愛情觀" ("Seeing Pu Songling's Social Background and Views on Love from 'The Young Gentleman from Jiaping'") that has a 9 endnotes and an extensive bibliography of works cited and consulted. Another essay "探討<霍小玉>中所映照的唐代社會" (An Exploration of Tang Dynasty Society as Reflected in Huo Xiaoyu"), written for the same professor, also looks like a research paper. These are both analyzing literary works in relation to their social contexts (and they were both written by students in the Chinese Department).

So there are at least three essays that look like academic essays in which outside sources are footnoted and listed in bibliographies. There might be more, but I haven't had time to go through all of the essays. (Note that I'm not being critical of the other types of writings in this collection--the sanwen and poetry, for example--I'm just trying to get a sense of the range of genres in these "加強寫作班.")

Friday, January 25, 2013

Notes about chapter one of Asia as Method

Chen, Kuan-Hsing. "The Imperialist Eye: The Discourse of the Southward Advance and the Subimperial Imaginary." Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2010. 17-64.

In this chapter Chen takes as his object of analysis five essays published in a special literary supplement to The China Times (中國時報) published in 1994. He uses his analysis of these articles to argue that they provide cultural/scholarly support for a Taiwanese nationalist subimperialist project of economic penetration into Southeast Asia. The perspective behind this support, Chen argues, is only possible by virtue of the historical blinders the writers (whom he calls "self-proclaimed 'native leftists'" [26]) wear. These blinders allow the writers to ignore how the "southward advance" was based on the 1930s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere that was a Japanese imperialist project.

Here are some quotes from this chapter (I don't intend this to be comprehensive):

Earlier, he writes that during the martial law period of the Chiangs, the government's "Chinese chauvinism" made use of "White Terror totalitarianism" that

In this chapter Chen takes as his object of analysis five essays published in a special literary supplement to The China Times (中國時報) published in 1994. He uses his analysis of these articles to argue that they provide cultural/scholarly support for a Taiwanese nationalist subimperialist project of economic penetration into Southeast Asia. The perspective behind this support, Chen argues, is only possible by virtue of the historical blinders the writers (whom he calls "self-proclaimed 'native leftists'" [26]) wear. These blinders allow the writers to ignore how the "southward advance" was based on the 1930s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere that was a Japanese imperialist project.

Here are some quotes from this chapter (I don't intend this to be comprehensive):

In Taiwan, the third world never became a critical-analytic or political category. Politicians, intellectuals, and business people have always identified themselves with advanced, first-world countries and felt it shameful to be put into the category of the third world. The absence of a third-world consciousness has been a basic condition of intellectual life in Taiwan, including among left-leaning circles. This absence, I wish to argue, was a necessary condition for the formation of the southward-advance discourse. (20-21)

In the field of cultural studies, the third world as an analytical category has also been ignored. Although, since the 1990s, this field has been going through a period of internationalization, the third world has not been taken up as a coordinating concept around which to organize dialogue. This has immense methodological and political consequences. (21)

[In his essay, "Gazing at Low Latitudes: Taiwan and the 'Southeast Asia Movement,'" Yang Changzhen] cites archeological and anthropological evidence to argue that a group of Taiwan's aboriginal tribes called the Pingpu "belong to the Malay race." ...The discursive effect is to naturalize Taiwan's rightful place as an original part of the Southeast Asian black-tide cultural sphere and attribute its later Chinese affiliation to human factors. ... Throughout the rest of the narrative, Taiwan is homogenized, a place completely deprived of social differences. Yang's starting point could have led him to argue for the restoration of Taiwan's territory and sovereignty to "nature," or to the "real" Taiwanese--that is, the aboriginal tribes. But he deploys the aboriginal figure only for the purpose of connecting the Han Chinese Taiwan with Southeast Asia. There is no reflection on the Han Chinese colonization of Taiwan's aboriginal population. (30-1)

The field of Taiwanese history has grown quickly since previously forbidden topics such as the 228 Incident and the White Terror became available for investigation. A more pervasive but little-noticed movement was the emergence of local history groups, which work throughout the island at the village level to collect materials, chronicle local events, and in the process build a cultural identity. This massive writing is evidence of the current struggle over who has the power to interpret history. The interpretations are clearly oriented toward the future, not mere retracings of a suppressed past; most originate from a particular political position or ideology and are used to support political or ideological goals, including the dream of an independent nation, the consolidation of state power, and a combination of the two. The most important function of historical interpretation is to selectively organize popular memory. As critics of the society, we are fortunate to be able to watch these processes in action and see firsthand how collective memory does not just exist "out there," but is constructed and reconstructed through the writing of the past into the present. (62-3)Some of this last quotation is on one level obvious to anyone who studies rhetorical history; on another level, it strikes me that Chen himself has done some historical interpretations in this chapter. What "particular political position or ideology" is he writing from?

Earlier, he writes that during the martial law period of the Chiangs, the government's "Chinese chauvinism" made use of "White Terror totalitarianism" that

led to appalling mutilation of the collected psychic structure, mutilation that can be seen in today's warped modes of communication, suspicion of other people, and alienation. Such fascist cultural forms as the patriarchal mind-set, whisper campaigns, dividing others into either friends or enemies, and surreptitious defamations still operate in Taiwanese society. Even progressive social movements in the civil society are not exempt from these fascist currents. (58)He goes on, then, to argue that the KMT's "Chinese chauvinism" was replaced by Taiwanese nationalism that is characterized by an "ethnic chauvinism ... [that] is exemplified in the adversarial relationship between native Taiwanese and mainlander ..." (59).

The reservoir of discontent that the colonized had for years been accumulating was co-opted by the ruling bloc. The co-optation made possible intimate links between Taiwanese nationalism, statism, and colonial imperialism, while ideologically constituting the desire for the formation of the Taiwanese subempire. (61)I'll have to read the next chapter to see if this all gets clearer...

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Some quotes from the introduction to Kuan-Hsing Chen's Asia as Method

Here are a few quotes from the introduction ("Globalization and Deimperialization") to Kuan-Hsing Chen's book, Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2010), 1-16.

More as I finish other chapters in this book...

"If postcolonial studies is obsessed with the critique of the West and its transgressions, the discourses surrounding globalization tend to have shorter memories, thereby obscuring the relationships between globalization and the imperial and colonial past from which it emerged." (2)

"The epistemological implication of Asian studies in Asia is clear. If "we" have been doing Asian studies, Europeans, North Americans, Latin Americans, and Africans have also been doing studies in relation to their own living spaces. That is, Martin Heidegger was actually doing European studies, as were Michel Foucault, Pierre Bourdieu, and Jurgen Habermas. European experiences were their system of reference. Once we realize how extremely limited the current conditions of knowledge are, we learn to be humble about our knowledge claims. The universalist assertions of theory are premature, for theory too must be deimperialized." (3)

"My use of the word 'globalization' does not imply the neoliberal assertion that imperialism is a historical ruin, or that now different parts of the world have become interdependent, interlinked, and mutually beneficiary. Instead, by globalization I refer to capital-driven forces which seek to penetrate and colonize all spaces on the earth with unchecked freedom, and that in so doing have eroded national frontiers and integrated previously unconnected zones. In this ongoing process of globalization, unequal power relations become intensified, and imperialism expresses itself in a new form." (4)

"Current decolonization movements must confront the conditions left behind by the cold-war era. It has become impossible to criticize the United States in Taiwan because the decolonization movement, which had to address Taiwan's relation with Japan, was never able to fully emerge from the postwar period; the Chinese communists were successfully constructed as the evil other by the authoritarian Kuomintang regime; and the United States became the only conceivable model of political organization and the telos of progress. Consequently, it is the Chinese mainlanders (those still in China as well as those who moved to Taiwan in 1949) who have, since the mid-1980s, become the figures against whom the ethnic-nationalist brand of the Taiwanese nativist movement has organized itself. In contrast, the Americans and Japanese are seen as benefactors, responsible for Taiwan's prosperity." (9-10)(I hope he gives a more nuanced account later on of what he says rather sweepingly in this paragraph. I can see his point, but I think it's overstated.)

More as I finish other chapters in this book...

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

More notes?

Thinking of firing up the blog again after a long period of sporadic posts. Don't know if anyone is still following this, but maybe if I write something worth reading, some readers will show up. And if I don't, well...

I'm not sure what to write about yet, though. Perhaps I'll post some notes about books I'm reading, just to get started. We'll see...

I'm not sure what to write about yet, though. Perhaps I'll post some notes about books I'm reading, just to get started. We'll see...

Sunday, December 02, 2012

CFP: Orienting Orwell: Asian and Global Perspectives on George Orwell

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies

Vol. 40 No. 1 | March 2014

Guest Editors: John Rodden & Henk Vynckier

Deadline for Submissions: August 15, 2013

While George Orwell’s status in Britain, the US, and the West generally speaking is beyond question, his place in Asian and other non-Western cultural discourses has been less certain. From raucous democracies to hermit kingdoms, contemporary Asia features varied societal and political models, and George Orwell’s writings consequently have been received very differently from country to country. For example, in Myanmar, the former Burma, Burmese Days (1934) is hailed as a first-class anti-colonial document, but Animal Farm, Nineteen Eighty-four, and the rest of his work are banned.

To be sure, Orwell is profoundly linked to and deserving of consideration in the Asian cultural context. He was born in Bengal, served five years in the Indian Imperial Police in Burma, and returned from the experience a firm anti-colonialist. Already in his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), he reflected on the fate of Indian rickshaw pullers and gharry ponies while discussing his experiences as a dishwasher in Paris, and such texts as “A Hanging,” “Shooting an Elephant,” and Burmese Days have become classics of English colonial literature. From 1941 to 1943 he was employed by the Indian section of the BBC’s Eastern Service. His private correspondence, book reviews, and essays further demonstrate his lifelong interest in the question of Indian independence, the future of Palestine, decolonization throughout Asia and around the world, and new English writings from Asia. Yet in Nineteen Eighty-four, a very different Asia looms large, for Oceania, the Anglo-American superpower in this dystopian classic, is permanently threatened by the two rival global powers of Eurasia and Eastasia.

The purpose of this special issue is to invite essays that further Orwell scholarship in an Asian as well as global context and, in doing so, make possible new perspectives on one of the most influential authors of the 20th century.

**********

John Rodden is an independent scholar located in Austin, Texas. He has taught at the University of Virginia, the University of Texas at Austin, and Tunghai University in Taichung, Taiwan. He has published ten books on Orwell, including The Politics of Literary Reputation: The Making and Claiming of “St. George” Orwell (1989) and The Cambridge Introduction to George Orwell (2012). He has also published critically acclaimed monographs on the New York intellectuals, the politics of culture in Germany before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the art of the literary interview.

Henk Vynckier is the Chair of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature at Tunghai University, Taichung, Taiwan. He has published on Orwell, collecting as a literary theme, travel literature, and the literary legacy of the Chinese Maritime Customs Agency (1854-1950). He is also an honorary researcher in the Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences at the Academia Sinica contributing to an interdisciplinary research project on Robert Hart and the Chinese Maritime Customs Service.

**********

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies is a peer-reviewed journal published two times per year by the Department of English, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan. Concentric is devoted to offering innovative perspectives on literary and cultural issues and advancing the transcultural exchange of ideas. While committed to bringing Asian-based scholarship to the world academic community, Concentric welcomes original contributions from diverse national and cultural backgrounds.

Each issue of Concentric publishes groups of essays on a special topic as well as papers on more general issues. The focus can be on any historical period and any region. Any critical method may be employed as long as the paper demonstrates a distinctive contribution to scholarship in the field.

For submissions guidelines and other information, please visit our website:

http://www.concentric-literature.url.tw/

Tuesday, November 13, 2012

Another Oysters Update

A while back, I came across the name of John Caldwell in reference to Vern Sneider's A Pail of Oysters. As I wrote then, Caldwell, who was a former State Department official, had testified to a US Senate subcommittee in 1954 about the effects of Communism on the US publishing industry in regards to Asia.

Yesterday Caldwell's name popped up again in a search I did about Vern Sneider. I've been looking for information on the possible effects of publishing Oysters on Sneider's writing career. I haven't found anything yet. But I did see a reference to Sneider in a book that Caldwell wrote. In 1955, Caldwell published a book entitled Still the Rice Grows Green that's available online. The first sentence of the book gives a sense of where Caldwell is going to go with this:

In his book, he makes brief reference to Sneider in one of the two chapters about Taiwan.

As Caldwell finds, of course, things are different that Sneider depicts them:

Caldwell manages to leave out Chiang's role in creating the "scars" that are easily blamed on Chen Yi. He also argues,

Yesterday Caldwell's name popped up again in a search I did about Vern Sneider. I've been looking for information on the possible effects of publishing Oysters on Sneider's writing career. I haven't found anything yet. But I did see a reference to Sneider in a book that Caldwell wrote. In 1955, Caldwell published a book entitled Still the Rice Grows Green that's available online. The first sentence of the book gives a sense of where Caldwell is going to go with this:

IF THE DAY be bright and clear, the pilot flying the lonely skies from Formosa westward to the China Coast sees the mainland of Enslaved China even before the lofty peaks of Free China recede into the haze.

In his book, he makes brief reference to Sneider in one of the two chapters about Taiwan.

I had just read parts of a new book, had read a number of rave reviews about the book. Written by Vern Sneider and called A Pail of Oysters, the book took some pretty terrific swipes at Free China's government and particularly at the military. Mr. Sneider had, I knew, spent several weeks on Formosa before completing his book. It was fiction, to be sure, but surely no American writer would completely falsify, even in a novel!

As Caldwell finds, of course, things are different that Sneider depicts them:

The Chinese GI is kept very busy. When not working or maneuvering, he studies. Literacy among the rank and file is now 94 per cent* He has no time off, has no chance to go to towns and cities and get in trouble. He is well fed, well clothed, and the temptation to steal has been removed. Above all he has a self-respect he never had before. He knows that he will be paid what little he is due regularly. He knows he will have reasonable medical attention when ill. Certainly his life is hard, but he knows that he is as well off as most of the civilian population. He has learned to work with the civilian population, to respect its rights.Chen Yi gets a mention, and Caldwell does have criticism for the way the Nationalists ran things in China:

On this score Nationalist China has gone a long, long way indeed, Mr. Vern Sneider and his A Pail of Oysters to the contrary notwithstanding.

The mainland was lost in part because there were so many generals who were corrupt, so many other high officials with greedy hands. In my home province of Fukien I saw the Nationalist government at its worst, saw Governor Chen Yi and his henchmen milk the province dry.

Was Chen Yi dismissed? No, as was so often the case, he was promoted! Generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek made him Formosa's first governor at the end of World War II. And the exploitation of the island that took place under Chen Yi has left scars among the native Taiwanese that will require a generation to erase.

If Free China is to remain strong there must be no more Chen Yi's. Too often in the past Chiang Kai Shek has trusted old friends too much, has been so blinded by personal loyalty that he could not see their incompetence and corruption. But most of these old cronies are gone. Some, like Chen Yi, have been executed. Others stayed on under the Communists. Some have been kicked "upstairs" and are not in positions of influence and power.

Caldwell manages to leave out Chiang's role in creating the "scars" that are easily blamed on Chen Yi. He also argues,

The Nationalist Government does not run a police state. The very fact that the people to whom I talked were willing freely and openly to answer my questions should be an indication that people feel free. There is more and more freedom of the press, even vigorous criticism of government actions. For instance when a Communist plane flew over Formosa in September of 1954, the press vigorously criticized the government and the Chinese air force for not shooting it down.Hmmm... I'll let you draw your own conclusions...

Sunday, November 04, 2012

A few links about representation and advocacy

- "Advocacy and the informed outsider" (DJ Hatfield, Savage Minds, 2012)

- "Westerners on White Horses" (Nicholas Kristof, NY Times, 2010)

- "Nicholas Kristof's Advice for Saving the World" (Outside Magazine, 2009)

- "The White Savior Industrial Complex" (Teju Cole, The Atlantic, 2012)

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Pilgrimage

Little did I know when I was writing posts on this popular theme that they would culminate in a trip to this historic site:

How was I able to locate this sacred place? Research, my children! (OK, I googled it...)

Of course, as with all good pilgrimages worthy of the name, ours was fraught with danger (though that was mainly because I didn't have any coffee until we got to DD).

After our trip to DD, we found our way to a huge Chinese supermarket nearby. The selection of instant noodles alone was enough to make us 喜極而泣...

|

| Home of the first Dunkin' Donuts, Quincy, MA |

How was I able to locate this sacred place? Research, my children! (OK, I googled it...)

|

| A shot of the interior |

Of course, as with all good pilgrimages worthy of the name, ours was fraught with danger (though that was mainly because I didn't have any coffee until we got to DD).

After our trip to DD, we found our way to a huge Chinese supermarket nearby. The selection of instant noodles alone was enough to make us 喜極而泣...

Saturday, August 18, 2012

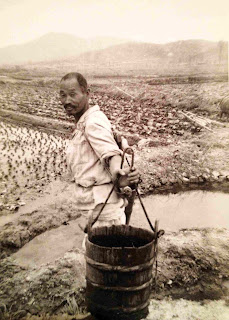

A few pictures from sixty years ago

On our most recent trip to my parents', we saw a few pictures that my late uncle took when he was stationed in South Korea during the Korean war. I thought I'd post a couple of them--I don't have much information about them, so if anyone has some information about where they might have been taken, etc., I'd appreciate your help.

Thanks to my wife for the 翻拍 and cropping!

First, a couple of pictures of my Uncle Warren and the notes he wrote on the back of them.

Neat handwriting, huh? Anyone who's been my student can tell you my handwriting is nowhere near as nice.

Somehow this (and the following pic) got through the Marines' censors...?

It might be hard to see the column of smoke...

I assume the following photos are from Korea, although my uncle did do some R&R in Japan. (He sent my mom some letters from there.) I'm particularly interested in the building in the last picture. Anyone know what it is?

Thanks to my wife for the 翻拍 and cropping!

Friday, July 27, 2012

Belated Note on Death of 邱永漢 (Kyu Eikan)

Just noticed today that 邱永漢 (Kyu Eikan) died back in May. Here's an English-language obituary. He's known for having been a novelist and a very successful investor. It mentions his involvement in the Taiwan Independence movement and his escape to Hong Kong, but doesn't mention his return to Taiwan in 1972. You'd have to read the Chinese-language Wikipedia article for details on that. The Wikipedia article discusses his "Taiwan Consciousness" (including his involvement with Thomas and Joshua Liao) and his escape to Hong Kong in 1948. It also relates his development in Japan as a writer and investor. There's also a link to a 1972 news video about Kyu's return into "the embrace of the fatherland..." (As readers of this blog--any still out there?--probably know, the aforementioned Thomas Liao had already returned to Taiwan in 1965 after living in Japan as the President-in-Exile of the Republic of Formosa. There's news video on that, too.)

Kyu had been a student of George Kerr when Kerr was teaching in Taiwan in the late 1930s. They kept in touch over the years, and Kyu mentioned Kerr (fictionalizing his name, according to Kerr, to either "Lloyd" or "White") in a short novel he wrote about 228 and its aftermath, entitled 濁水溪. (The link is to a site selling the Chinese translation of Kyu's Japanese-language novel.) Kyu was also interested in helping Kerr translate Formosa Betrayed into Japanese, but that project never panned out.

When Thomas Liao returned (surrendered?) to Taiwan in 1965, Kerr wrote to Kyu (among others) to ask what had happened and what the implications might be for the Taiwan Independence Movement. Kyu was still in Japan at the time. He wrote back to Kerr, highlighting some of the factionalism in the Japanese TIM, including the bad relations between Liao and himself. Kyu wrote that Liao "had been jealous to my fame, my little success in Japan." He noted that "[m]any political refugees who at first participated in his [Liao's] provisional government, quarrelled with him and left him." He felt that the movement would become stronger in Liao's absence. He concluded,

(Quotes are from Kyu's letter to "Kerr Sensei" from June 4, 1965. The letter is found in the George H. Kerr papers in the Okinawa Prefectural Archives.)

Kyu had been a student of George Kerr when Kerr was teaching in Taiwan in the late 1930s. They kept in touch over the years, and Kyu mentioned Kerr (fictionalizing his name, according to Kerr, to either "Lloyd" or "White") in a short novel he wrote about 228 and its aftermath, entitled 濁水溪. (The link is to a site selling the Chinese translation of Kyu's Japanese-language novel.) Kyu was also interested in helping Kerr translate Formosa Betrayed into Japanese, but that project never panned out.

When Thomas Liao returned (surrendered?) to Taiwan in 1965, Kerr wrote to Kyu (among others) to ask what had happened and what the implications might be for the Taiwan Independence Movement. Kyu was still in Japan at the time. He wrote back to Kerr, highlighting some of the factionalism in the Japanese TIM, including the bad relations between Liao and himself. Kyu wrote that Liao "had been jealous to my fame, my little success in Japan." He noted that "[m]any political refugees who at first participated in his [Liao's] provisional government, quarrelled with him and left him." He felt that the movement would become stronger in Liao's absence. He concluded,

I just remind 17 years ago when I took refuge in HongKong, called upon Liao and wrote the MS for the petition to the UN. At that time the paper in HK and Formosa said our thinking and intentions[?] was lunatic, but now KMT people have endorsed our movement by buying off Liao.After reading Kyu's comments about Liao's defection, I'm curious as to why Kyu himself went back to Taiwan seven years later. Even Kerr was surprised about this turn of events.

(Quotes are from Kyu's letter to "Kerr Sensei" from June 4, 1965. The letter is found in the George H. Kerr papers in the Okinawa Prefectural Archives.)

Thursday, April 26, 2012

CFP: "Documenting Asia Pacific"

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies

Vol. 39 No. 1 | March 2013

Special Issue Call for Papers

“Documenting Asia Pacific”

Guest Editors: Kuei-fen Chiu & Chi-hui Yang

Deadline for Submissions: August 15, 2012

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies is a peer-reviewed journal published two times per year by the Department of English, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan. The journal is devoted to offering innovative perspectives on literary and cultural issues and advancing the transcultural exchange of ideas.While committed to bringing Asian-based scholarship to the world academic community, Concentric welcomes original contributions from diverse national and cultural backgrounds.

The March 2013 issue of Concentric is dedicated to exploring new directions in documentary and non-fiction media-making practices in the Asia Pacific region. Dynamic political and economic conditions, innovations in production and distribution technologies, increased access to international finances and the migration of moving images from theatres to galleries to online spaces have made more relevant and critical the practice of documentary filmmaking in Asia Pacific.

The task of representing new social realities has generated significant movements—both political and aesthetic—in documentary filmmaking from Beijing to Manila, from Jakarta to Sydney. Engaged verite, documentary/fiction hybrids, personal essays and experimental collage are being used to explore the consequences of globalization and neo-liberalism, fraught family histories, religious conflict, and the role of the state in everyday lives. What kind of formal and aesthetic approaches are being developed to document the contemporary culture and politics of Asia Pacific? How is the documentary itself being tested and reshaped by these efforts? What might be revealed from a study of localized movements, and what might comparative studies across national or cultural boundaries yield?

Concentric invites examinations of all aspect of contemporary documentary and non-fiction media-making in the Asia Pacific region.

*******************

Kuei-fen Chiu is Distinguished Professor of Taiwan Literature and Transnational Cultural Studies at National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan specializing in Taiwan literature and documentary film. In addition to several books in Chinese, she has published with international journals including The Journal of Asian Studies, The China Quarterly, and Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies. She is a multi-time recipient of the prestigious national award for excellence in research in Taiwan and was Honorary Fellow at the Center for Humanities Research at Lingnan University, Hong Kong for the period 2008-2011. Several of her articles have been translated into Japanese.

Chi-hui Yang is a film programmer, lecturer and writer based in New York. His curated programs have been presented at MoMA Documentary Fortnight, the Robert Flaherty Film Seminar, UnionDocs, Washington DC International Film Festival, and Seattle International Film Festival. From 2000 to 2010 he was the Director and Programmer of the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival, the largest showcase of its kind in the US. He is currently a visiting scholar at NYU’s Asian/Pacific/American Institute.

*******************

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies

Manuscript Submission Guidelines

1. Manuscripts should be submitted in English. Please send the manuscript, an abstract of no more than 250 words with 5-8 keywords, and a brief curriculum vitae as Word attachments to [no e-mail address given]. Please also attach a cover letter stating that the manuscript is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere. Concentric will acknowledge receipt of the submission but will not return it after review.

2. Submissions made to the journal should generally be at least 6,000 words but should not exceed 10,000 words, notes included; the bibliography is not counted. Manuscripts should be prepared according to the latest edition of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. Except for footnotes, which should be single-spaced, manuscripts must be double-spaced throughout and typeset in 12-point Times New Roman. For further instructions on documentation, consult our style guide.

3. To facilitate the journal’s anonymous refereeing process, there must be no indication of personal identity or institutional affiliation in the manuscript proper. The author may cite his/her previous works, but only in the third person.

4. If the paper has been published or submitted elsewhere in a language other than English, please also submit a copy of the non-English version. Concentric may not consider submissions already available in other languages.

5. If the author wishes to include copyrighted images in the essay, the author is solely responsible for obtaining permission for the images.

6. Two copies of the journal and a PDF version of the published essay will be provided to the author(s) upon publication.

7. It is the journal’s policy to require all authors to sign an assignment of copyright.

For submissions or general inquiries, please contact us as follows:

Editor, Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies

Department of English

National Taiwan Normal University

162 Heping East Road, Section 1

Taipei 106, Taiwan

Phone: +886 (0)2 77341803

Fax: +886 (0)2 23634793

E-mail: concentric.lit@deps.ntnu.edu.tw

For other information about the journal, please visit our website

Friday, February 10, 2012

Facing history

Sayaka Chatani's recent post mentioning the idea of running a history/critical thinking summer camp for high school students from Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan reminded me of an Oberlin College graduate's "rep letter" from the '50s about a workcamp and seminar for Asian college students run in Japan by the American Friends Service Committee. (Chew on that sentence for a while...) The rep letter, by Ray Downs, who was an Oberlin Shansi rep at Obirin Gakuen, was reprinted in Something to Write Home About: An Anthology of Shansi Rep Letters, 1951-1988.

In Chatani's post, she wrote that one of the difficulties she imagines with running a summer camp like this is that she doesn't know

In Chatani's post, she wrote that one of the difficulties she imagines with running a summer camp like this is that she doesn't know

how to lead the history workshop to constructive critical thinking, instead of creating the clear-cutting aggressor-vs-victim narrative. (Ugh, this positionality issue, again.)The rep letter by Downs is concerned with a meeting at the work camp among college students from Japan, the U.S., India, Vietnam, Malaya, Thailand, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Canada, and Hawaii. The leader of the meeting, a Fulbright scholar named John Howes, wanted the participants to discuss tensions that might have remained after the war. As Downs writes (and recall, this was written in 1955),

Howes was interested in bringing emotions themselves to the surface rather than discussing issues in which emotions were involved only indirectly insofar as they influenced opinion. For a time it seemed that he would be unsuccessful. Discussion moved along on a relatively scholarly and impersonal level. I began to think that most of those present, like myself, had ceased to think of the last war except as history, since it all was over before most of them were twelve years old. I asked a question to this effect. I had been wrong. (14)After Downs asked the question, the participants began to open up about their experiences, telling about how their families and friends had suffered. As Downs writes,

... I think a new dimension had been added to the understanding of all of us. Certainly in parts of Asia the scars of war have not all disappeared with reconstruction. I think we all learned something more of the horror of war in its varied manifestations. (15)Interestingly, he concludes that the participants were still able "to work and live happily together" even after the stories they told that evening,

and within a day or two there seemed to be a new depth in our sense of community. Before I left I began to appreciate more fully the role of this kind of experience as a means toward the greater end of increased understanding. (15)I don't know if there are still camps like this, but a couple of thoughts occurred to me in comparing the experience Downs had with Chatani's concern about the "aggressor-vs-victim narrative," both of which revolve around questions about memory and "the scars of war." How did the university students manage to "work and live happily together" only ten years after the war, when they had witnessed with their own eyes atrocities committed by their fellow participants' countrymen? How could feelings about an event become even stronger decades after the event, when most of the survivors had died and the people with the strong feelings had little or no direct experience of that event? Note that I am not trying to be cynical about this.

Sunday, January 22, 2012

CFP: Academic Writing Theory and Practice in an International Context

In the autumn of 2012, The Centre for Academic Writing at Coventry University will launch the first taught postgraduate programme in Academic Writing in the UK and Europe: The MA/PG Diploma in Academic Writing Theory and Practice/The PG Certificate in Academic Writing Development. To mark the launch of this programme, we are organising a one-day conference, with the theme, ‘Academic Writing Theory and Practice in an International Context’.

We invite 20-minute presentations (followed by 10 minutes of discussion) on research into academic writing as text, process and practice, within national and/or international contexts. The sub-themes of the conference are:

The keynote speaker of the conference is Dr. Theresa Lillis from the Centre for Language and Communication at the Open University, UK. Dr. Lillis has published research on student and professional academic literacies and is the author of Student Writing: Access, Regulation, Desire (Routledge, 2001) and, with Mary Jane Curry, Academic Writing in a Global Context: The Politics and Practices of Publishing in English (Routledge, 2010).

- Forms and practices of disciplinary and interdisciplinary writing

- Teaching and developing student and professional academic writing

- Rhetoric and academic writing

- Writing/publishing in English as an academic lingua franca and the trans-nationalisation of knowledge

- Writing programme development and management

The conference panels as communities of knowledge and practice!

We would very much like the panels of the conference to become small interpretive communities through the dialogues between panellists and their audience. We encourage participants, whether presenters or non-presenters, to remain in the panels they choose to attend and engage with the topics and ideas of the respective panel.

Non-presenters who would like to share in the conference discussions are also invited to attend.

Proposals and Registration

To submit a proposal, please email a 250-word abstract to writing.caw@coventry.ac.uk by 31 January 2012. We will send you a response by 5 March 2012.

Registration for the conference will be open between 5 March and 10 April 2012. The registration fee is £45 (British Pounds Sterling). Payment and booking details will follow at a later date.

Friday, January 20, 2012

Tuesday, January 03, 2012

快要開學了

我最近在想,用第二個語言(或者第三,四,五個語言)寫作要經過多少翻譯 呢?像我 , 為了寫我剛剛寫的句子,必須先用英文想 , 想到了以後開始慢慢地翻 , 結果我寫到的中文句子跟我原來用英文想的句子不太一樣 。 這可能是因為我寫的時候 , 忘記我本來在想甚麼。

我們快要開學了。

我們快要開學了。

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)